Tail Risk 2024.

Bridgewater previews the upcoming elections.

This was posted yesterday (verbatim) at Political News Items, which we distribute 2 or 3 times a week (at the moment). Political Items covers politics, domestic and foreign. Our premise is that politics, domestic and foreign, is being massively disrupted and recklessly practiced. And that the results of disruption and malpractice are upon us. And that it will get worse before it gets better. If it gets better.

One thing we’re hoping to do with Political News Items is bring to your attention political analysis and commentary from sources you might not know of or expect to hear from. What follows are excerpts from yesterday’s edition of Bridgewater’s “Daily Observations” newsletter. It looks at the state of the (2024) race and the policy differences and risks associated with the leading candidates.

Bridgewater is the world’s largest hedge fund. It is known for its rigorous research. It is staffed, as you might imagine, by legions of very smart people. The excerpts that follow are re-published with the firm’s permission. “Daily Observations” is paywalled by the firm and unavailable on the web.

All that said, let’s get started.

Bridgewater Daily Observations newsletter, 17 July 2023:

With a good chance that we will see a Biden-Trump rematch, we’ve revisited some of the key policy contrasts and similarities from their respective terms and share our thoughts on implications for investors going forward. In brief:

Biden and Trump each ran relatively stimulative and activist fiscal policies during their first terms, with Trump enacting substantial tax cuts and Biden driving multiple spending bills across the COVID recovery, infrastructure, manufacturing, and green energy. We expect a second Trump/Biden administration to continue to favor their preferred mix of taxes and spending (with Trump’s individual income tax cuts scheduled to lapse at the end of 2025), while facing stronger headwinds against enacting additional stimulus (outside of an economic crisis) from record non-wartime structural deficits and still above-target rates of inflation.

Regarding foreign policy, there has been an almost unidirectional shift toward more strained relations with China over the last five years. While the Trump administration was more inclined to go it alone with an “America First” approach, the Biden administration has focused on building alignment with key US allies and partners. We would expect more of the same with another Biden administration, while a second Trump administration would more likely than not move to unwind this return to greater alliance building and create a wider cone of outcomes vis-à-vis China and Russia.

The upcoming election serves as a potential flashpoint for the ongoing shift in US politics toward extreme polarization, partisanship, and the risk of political instability, as we saw in stark terms during the 2020 presidential election. A close race with Trump, win or lose, again heightens risk of one side or the other contesting or not accepting the result. We’d also expect a second Trump term to result in further degradation of several longstanding US government institutions and norms (e.g., Trump’s plan to disempower the administrative state) and an increased risk of visible political conflict and instability.

Each of these dimensions creates risk and uncertainty for investors, with a second Trump presidency (particularly if paired with a Republican House and Senate) generating much bigger shifts in domestic and foreign policy and raising the risk of a more serious disruption to the increasingly polarized US political and governing system.

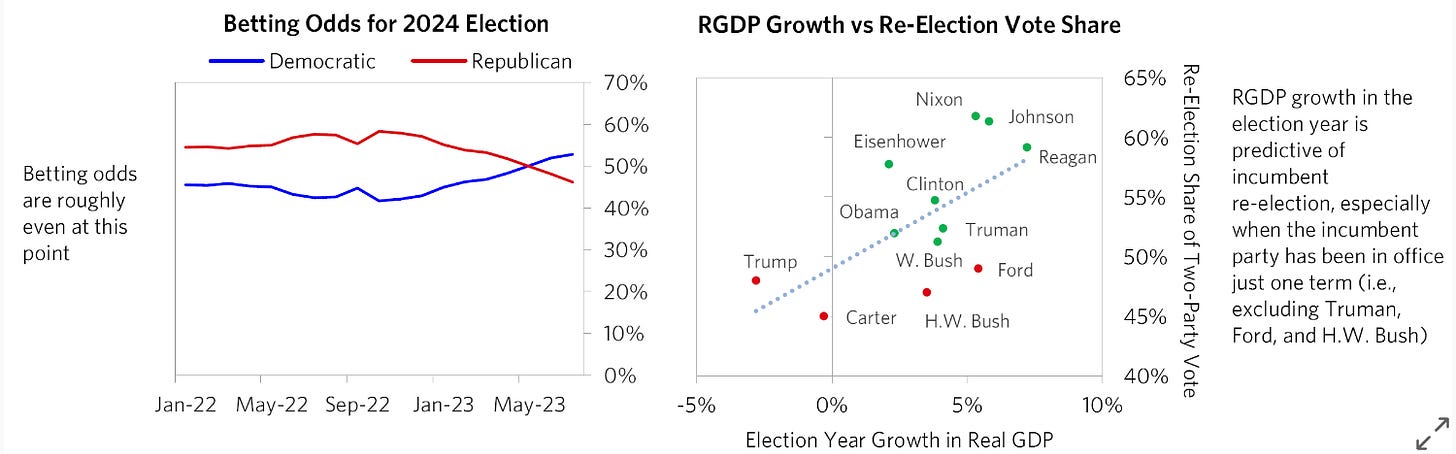

At this stage, the odds are roughly balanced between a Democrat and a Republican winning the presidency. Conditional on being the Republican nominee, Trump’s odds of winning the general election are around 37-45%, while DeSantis’s have fluctuated between 45% and 60%. If Trump were to lose the nomination, there is a possibility that he would run as a third-party candidate (as he attempted in 2000), likely retaining the support of much of his base and undercutting the Republican nominee. Economic outcomes in the lead-up to the election are likely to be significant in determining the result; as the chart below illustrates, election-year GDP growth is usually predictive of general election outcomes.

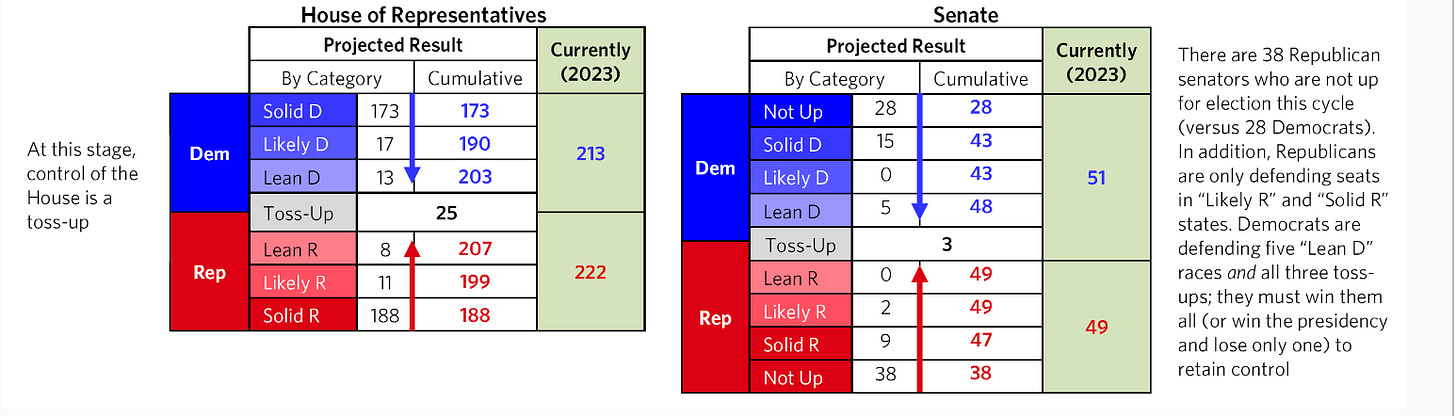

The congressional elections taking place on the same day are important and more likely to be overlooked. Congress will play a significant role in shaping the policy agenda and is a significant check on the executive (particularly in the context of divided government). At this point, the race for the House—in which Republicans currently have a small four-seat majority— is a toss-up that is likely to be correlated to the presidential result given historically low levels of split-ticket voting. That said, Republicans are likely to win the Senate, so the odds of a Democratic trifecta are low. Biden would need to win the popular vote by roughly 6 percentage points to achieve that, whereas he won by 4.5 points in 2020. This is because the Republicans have a significant structural advantage in the Senate race—23 of the incumbent Democratic senators are up for re-election, while only 11 of the incumbent Republicans are. To retain control of the Senate, Democrats must therefore run the table and win each of the Democratic-leaning seats as well as all three “toss-up” races (or win the presidency and lose only one).

US Political Stability, Institutions, and Governance

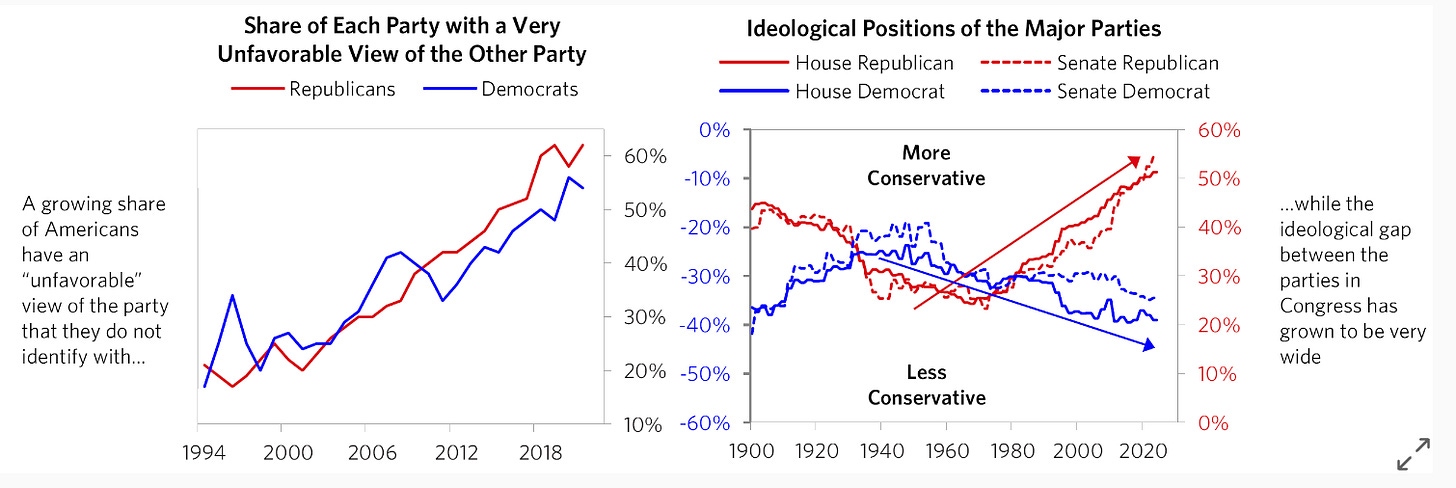

The US political system is now extremely polarized, and several of the customs, norms, and institutions that have long underpinned governance look much less robust going forward. In that context, the upcoming election raises another important set of tail risks and concerns for US economic and political governance, in turn creating risks for economic stability and for investors.

As the charts above illustrate, the political divide within the US has been growing for several decades, expanding further during the Trump presidency. Today, we see additional indications of this partisan divide metastasizing across multiple branches and levels of government, including:

The states operating in an increasingly partisan manner on traditionally federal or interstate issues (e.g., Texas and Florida have started relocating some migrants to blue states upon their arrival in the US).

The relationship between state political leadership and businesses becoming increasingly contentious on largely noneconomic issues (e.g., Florida—led by DeSantis—has feuded with Disney after Disney leadership commented on a Florida law).

Increased questioning of the operational independence of the Department of Justice from political leadership (e.g., Trump—who accuses Biden of having “weaponized” the DoJ—has vowed to reduce the independence of the FBI, as has DeSantis).

An increasingly dysfunctional relationship between the federal government and the states (particularly those governed by other parties). For example, a range of liberal jurisdictions refusing to cooperate with the federal government regarding certain deportation matters (e.g., California’s “sanctuary state” policy). While the federal government is responsible for border security and immigration, several Republican-governed states (including Virginia and South Dakota, as well as Texas) have now deployed their states’ National Guards to police the Mexican border.

Surveys reporting record-low trust in the Supreme Court, which has recently made a series of particularly consequential and controversial decisions—including last year’s reversal of Roe v. Wade—after Trump’s term established a 6-3 majority of Republican-appointed justices, while the more progressive left has pushed more assertively for changes to the design of the courts.

Looking ahead to an election with Trump as the Republican nominee or the possibility of a second Trump presidential term, we see more significant risks to US political and economic stability:

The most immediate tail risk is that there could be substantial nonacceptance of and conflict around the election result, particularly if the election is reasonably close. We saw this clearly in the aftermath of the 2020 election—culminating in a series of failed legal challenges associated with former President Trump, several other attempts to overturn the results, and the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021. The recent Electoral Count Reform Act may mitigate risks associated with Congress’s electoral count process (by addressing some of the ambiguities in the current statutory framework), and the midterm elections last November were relatively uneventful—but we’d expect this risk to become more salient again with Trump back on the ballot.

A second Trump administration would likely weaken longstanding rules that protect career civil servants from removal, increasing political control over the executive branch and posing a risk to the historically nonpartisan design of the administrative state. Near the end of his term, Trump instituted a policy known as “Schedule F,” which would have enabled easier removal of nonpolitical appointees in the federal civil service (who are generally protected from removal without cause). This was revoked by President Biden, but Trump has promised to “immediately reissue [that] executive order” in order to “dismantle the deep state” if elected again; this would reduce the bureaucratic guardrails that he believes he experienced in pursuing his agenda in his first term.